Burkina Faso, in the past few years, has become a beacon of hope for many throughout Africa who want their countries to take ownership of their own resources and reject colonial ideas left over from European occupation. It is to the north of Ghana, so I have heard about the country from my Dad for years, but I have never visited or even met anybody from there before.

I was scrolling through my phone, and in between exercise routines I’ll never do and clips of near-pointless politicians was a post about the decorated village of Tiébélé. I was fascinated by it, this artwork of a village. I was born in the UK, and we do not see buildings with this amount of decoration, detail and storytelling. Imagine if we took this approach and created buildings and villages that spoke to us beyond signage and materiality.

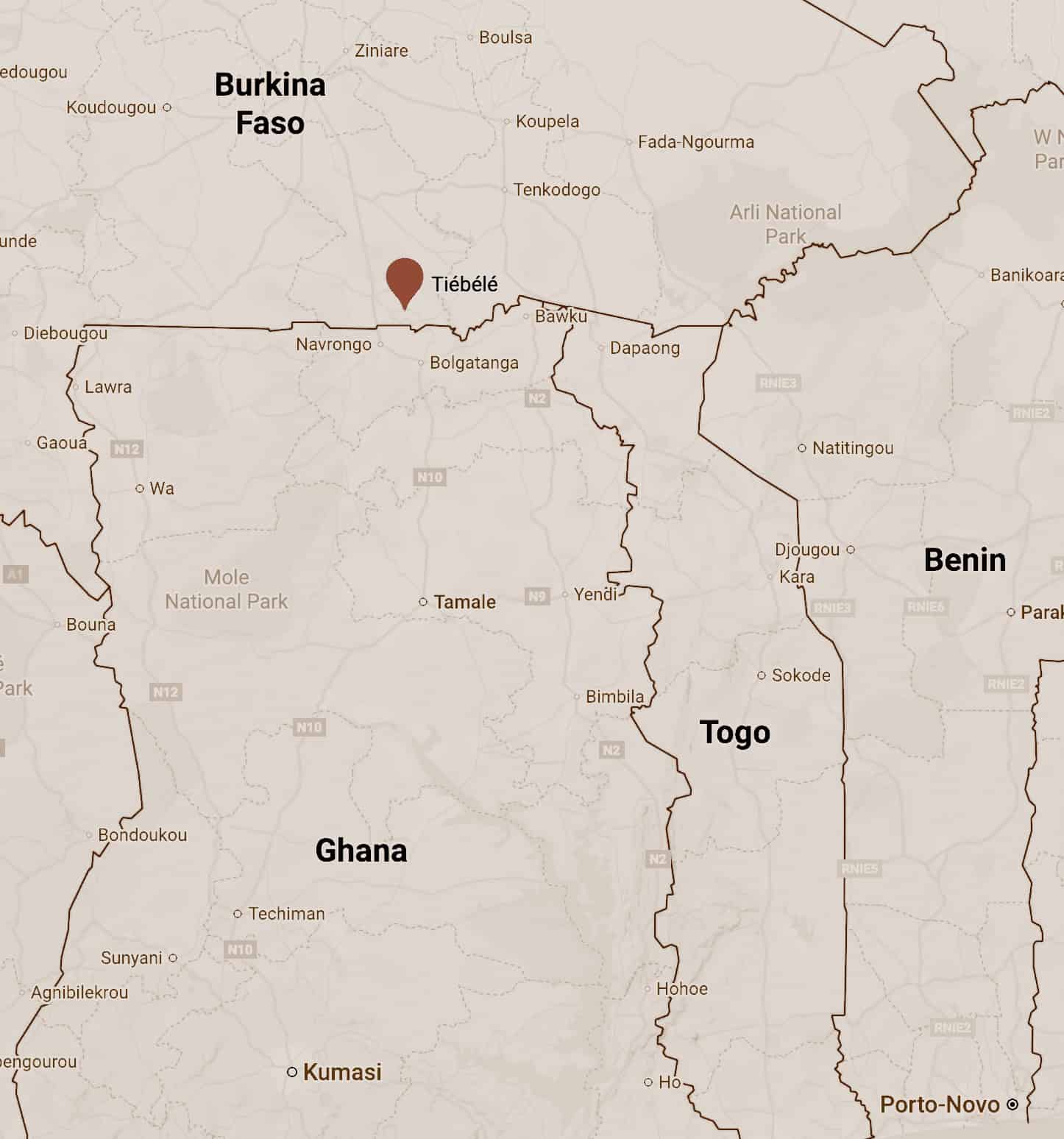

The village is in the south of Burkina Faso and close to the border with northern Ghana. I would love to combine a trip to both Bolgatanga (famous for its basket weavers and the home of AAKS) and Tiébélé at some point. The village was founded in the 16th century by the Kasena people. This is the case of each village they live in; Tiébélé is the most celebrated example.

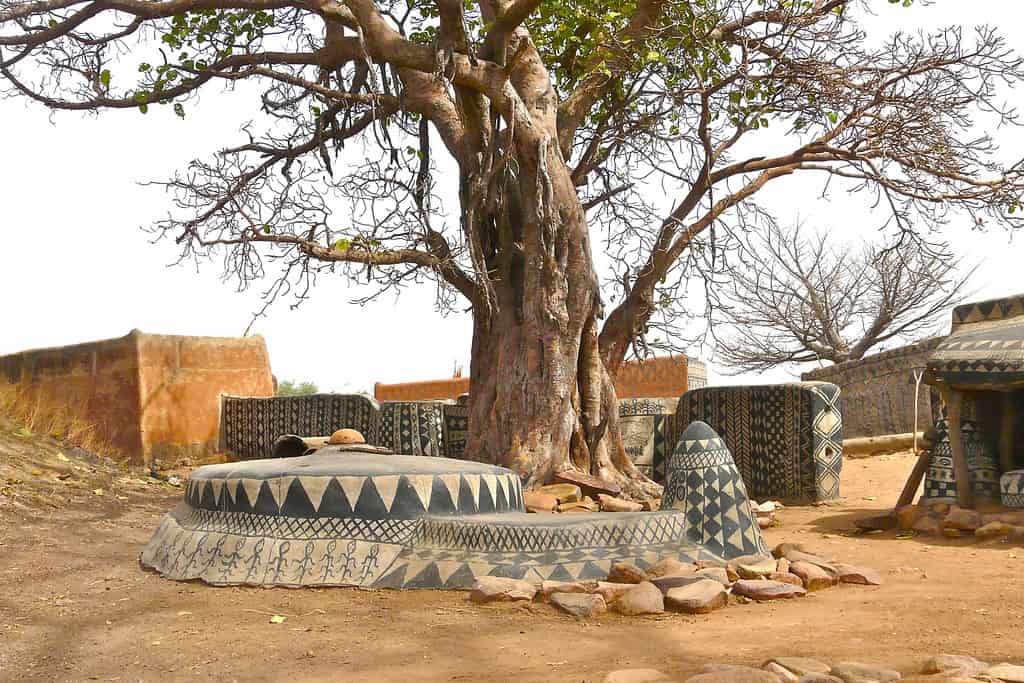

The architecture of Tiébélé is made up of buildings crafted from “mud”, ie, earth, straw, wood and cow dung. Mud has been used for centuries to create buildings throughout Africa. It’s an incredible formula that could only be created by people who know their land intimately.

The mud keeps houses cool when it needs to and warm when temperatures cool at night. Beyond its functional benefits, the architectural features reflect the craftsmanship involved in their creation. The softly sculpted corners and gentle indents demonstrate the care and attention given to each building.

The layout of the village is intentional and centred around shrines to God. The chief of the village lives in the Royal Court of Tiébélé, a complex with organically shaped rooms and intricate pattern work. Each building is designed to work hard for its occupants.

The architecture of the mud huts is as organic as the earth they are built on, with each structure having a distinct shape and specific reason behind it. Nothing is crafted by chance.

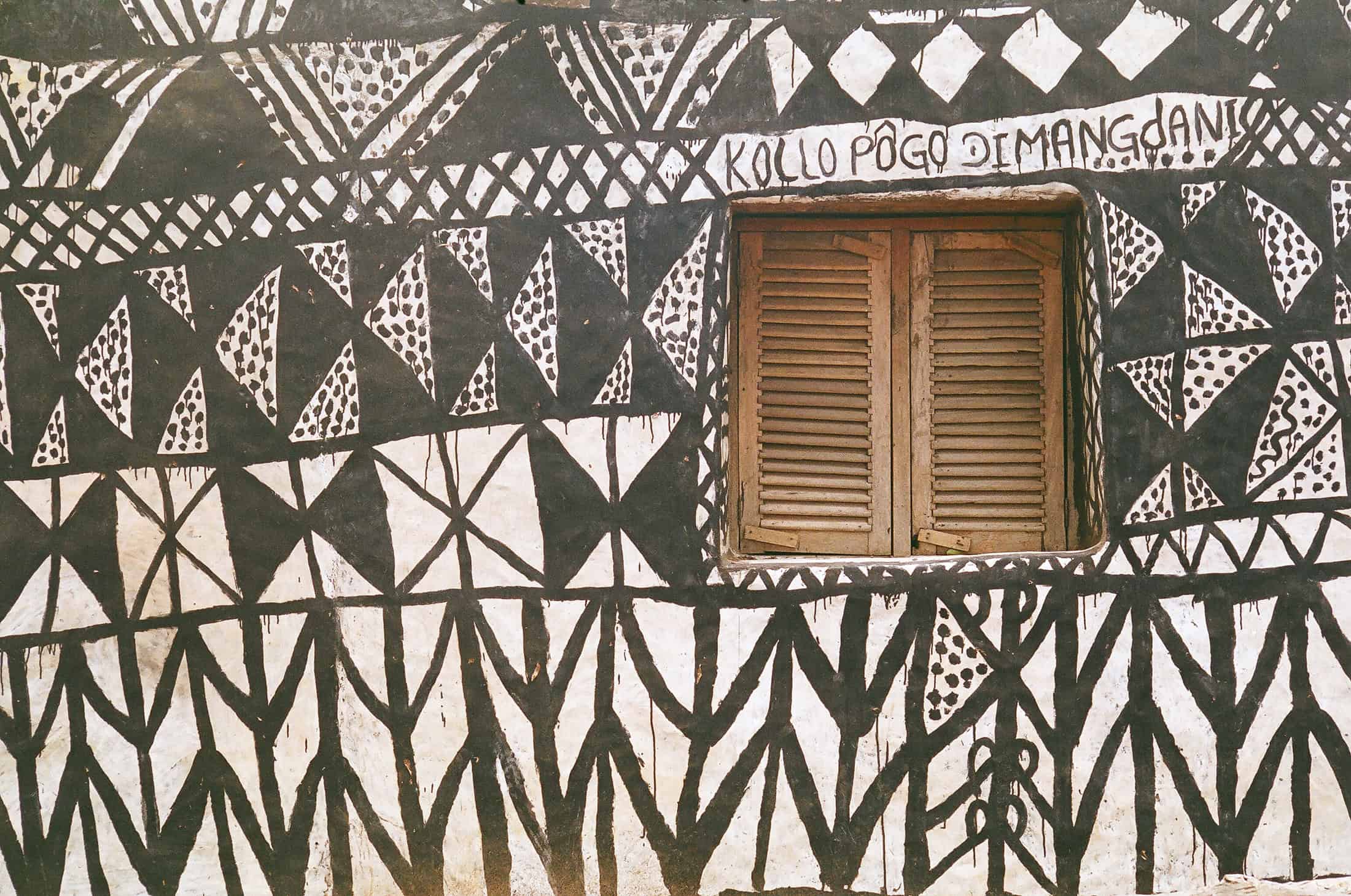

The patterns that decorate the walls are all painted by the women of the community. At first glance, it might seem like the patterns are random, but each house tells the story of each generation that has lived there. Symbols reflect stories and folklore passed down. Those stories are ongoing and held within each building.

The images above show the murals in more detail. The buildings are painted by hand, and you can see the way each of the patterns is unique. The patterns are re-painted every few years to maintain their detail.

Some patterns are painted straight onto the surface with a brush, others are rolled into fresh plaster, and some are sculpted so they actually stand out from the mud walls. Once the designs are ready, they’re finished with natural colours: red from laterite, white from kaolin clay, and black from graphite. These shades aren’t just for show; red stands for courage, white for honesty and purity, and black for the unseen world of night and spirits.

Each home in the village has its own language of symbols and patterns. You’ll spot stars and moons painted as signs of hope, arrows marking the house of a warrior, and sacred animals like crocodiles and snakes drawn to ward off illness and bad luck. Even the simpler shapes mean something—like a half-circle representing the humble calabash, an everyday object turned into a symbol.

There’s a human behind this artwork, and it’s not something we see much of in the UK. I would love to see some of this connection with our ancestors displayed on the outside and not just internally.

Sadly, the village is experiencing a challenge as the climate changes, as reported in The Guardian. As with us all, the health of the land is imperative to the livelihood of the community. It ot only provides materials to build the houses, but the formula needed to repaint he houses is derived from the earth… everything is connected.

As the crisis develops, we should all look to villages to see how this is affecting indigenous communities. The Kassena know their land, and this slow deterioration is a sign for us all.